The Hidden Agony of Dry Socket: Unveiling Its Complexities

Amidst the complexities following tooth removal, some individuals encounter an unexpected, lingering discomfort that goes beyond the typical healing process. This often results in heightened sensitivity and a noticeable, unpleasant scent, stemming from an improperly healing extraction site, leaving many in search of effective relief and understanding of the underlying issues.

The Biological Mechanics of Healing Failures

When the Protective Barrier Dissolves

The healing journey after a tooth is removed relies almost entirely on a single, fragile biological event: the formation of a blood clot. In the immediate aftermath of the procedure, this gelatinous clump acts exactly like a scab on a skinned knee. It serves as a natural biological bandage, sealing off the empty socket to protect the exposed bone and sensitive nerve endings underneath from air, food particles, and bacteria. Furthermore, this clot acts as the foundational scaffolding upon which new soft tissue and bone will eventually grow. However, in specific instances, this critical protective layer fails to develop correctly, or more commonly, is lost before the wound has stabilized.

The disintegration of this barrier is often driven by a physiological process known as fibrinolysis. Under normal circumstances, the body eventually breaks down blood clots once they are no longer needed, but in this condition, the process accelerates prematurely. Enzymes present in saliva or released by the tissues can attack the fibrin mesh that holds the clot together. When this mesh is dissolved, the clot liquefies and washes away, leaving the underlying structures perilously defenseless. This exposure is the primary source of the intense, radiating sensation patients feel, as the nerves are subjected to direct stimulation from the oral environment.

Understanding this chemical breakdown is crucial because it shifts the blame from "bad luck" to a specific biological sequence. It explains why the condition can occur even when a patient feels they have been careful. The balance between clot stabilization and clot dissolution is delicate, and when tipped by high levels of enzymatic activity, the socket is left empty, leading to the characteristic void that gives the condition its common name.

The Physics of Suction and Airflow

Beyond internal chemical reactions, simple physics plays a massive role in the stability of the extraction site. The mouth is a dynamic chamber where pressure changes constantly, and the newly formed clot is not anchored deeply into the tissue during the first few days. It sits loosely within the socket, making it highly susceptible to physical dislodgement caused by negative pressure or "suction." This is a mechanical failure rather than a biological one, yet the result is identical: the loss of the protective covering.

Everyday actions that seem harmless can generate significant intraoral vacuum force. Drinking through a straw is the most frequently cited culprit; the act of drawing liquid up a narrow tube requires a tight seal and strong suction, which acts like a vacuum cleaner over the wound site. Similarly, the aggressive spitting of toothpaste or vigorous rinsing to "clean" the wound can create enough hydraulic turbulence to wash the clot out. Even the act of dragging on a cigarette involves a suction motion that stresses the wound.

Invisible Triggers and Daily Habits

The Role of Bacteria and Hormonal Influence

While mechanical forces are visible and controllable, microscopic enemies also threaten the integrity of the healing site. The oral microbiome is vast, and certain strains of bacteria are particularly problematic for extraction wounds. Pre-existing infections, such as periodontal disease or pericoronitis (inflammation around wisdom teeth), leave a high load of bacteria in the mouth. These microorganisms can colonize the fresh wound and secrete enzymes that mimic the body's own clot-dissolving processes, essentially chemically digesting the protective plug from the outside in.

Furthermore, systemic factors within the body, specifically hormones, dictate how well the blood can clot and maintain that structure. There is a well-documented link between high estrogen levels and the breakdown of blood clots. This connection explains why specific demographics may statistically face higher complication rates. Estrogen can stimulate the fibrinolytic system (the clot-busting mechanism), making the clot more soluble and less stable. This is particularly relevant for individuals utilizing oral contraceptives, as the synthetic hormones can artificially elevate this risk during specific weeks of the cycle.

This intersection of bacterial load and hormonal environment suggests that the "health" of the extraction site is determined long before the tooth is actually pulled. Maintaining excellent oral hygiene to lower the bacterial count prior to surgery is a proactive defense. Similarly, discussing timing with a dental surgeon regarding the menstrual cycle or hormone medication usage can sometimes help in scheduling the procedure during a window where the body’s natural clotting ability is at its peak stability.

Lifestyle Choices That Impede Recovery

The influence of lifestyle on wound healing cannot be overstated, with tobacco use standing out as the single most detrimental factor. Beyond the physical suction mentioned earlier, the chemical impact of nicotine acts as a potent vasoconstrictor. When nicotine enters the bloodstream, it causes the tiny blood vessels in the gums and jawbone to clamp down. This constriction drastically reduces the flow of oxygen and nutrient-rich blood to the extraction site. Without a robust blood supply, the body cannot form a high-quality clot initially, nor can it bring in the immune cells needed to fight off infection and repair the tissue.

Dietary choices in the days following the procedure also act as a tipping point between recovery and complication. Consuming foods that are hard, crunchy, or crumbly (like chips, nuts, or popcorn) introduces physical debris that can become lodged in the socket. If a shard of food gets stuck in the healing wound, the body may react with inflammation, or the foreign object might physically disrupt the granulation tissue. Additionally, thermal shock from extremely hot liquids can dilate vessels and potentially dissolve the early clot structure.

Recognizing the Red Flags

Distinguishing Normal Soreness from Acute Complications

One of the most challenging aspects for patients is determining whether what they are feeling is part of the normal recovery curve or a sign that something has gone wrong. Standard extraction recovery usually involves a dull, throbbing ache that peaks within 24 hours and then gradually subsides. However, the condition in question presents a distinct timeline. A patient might feel they are recovering well for the first two or three days, only to be hit by a sudden, severe escalation of discomfort around day three or four. This delayed onset is a hallmark signature of the condition.

The nature of the sensation is also different. Rather than a localized soreness where the tooth used to be, this specific type of agony is often described as radiating or neuralgic. It shoots from the jaw up towards the ear, the temple, or down the neck. It is a deep, boring pain that feels like it is inside the bone itself—which, in reality, it is. Because the bone is exposed, the pain is often resistant to standard over-the-counter painkillers. If a patient finds themselves watching the clock for their next dose of medication and finding no relief, it is a strong indicator that the clot has failed.

| Feature | Normal Post-Extraction Healing | Complicated Healing (Dry Socket) |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of Pain | Immediate, peaking at 24 hours. | Delayed, appearing 3-5 days post-op. |

| Pain Quality | Dull, throbbing, localized. | Sharp, radiating to ear/eye, intense. |

| Response to Meds | Managed well with standard analgesics. | Resistant to OTC painkillers. |

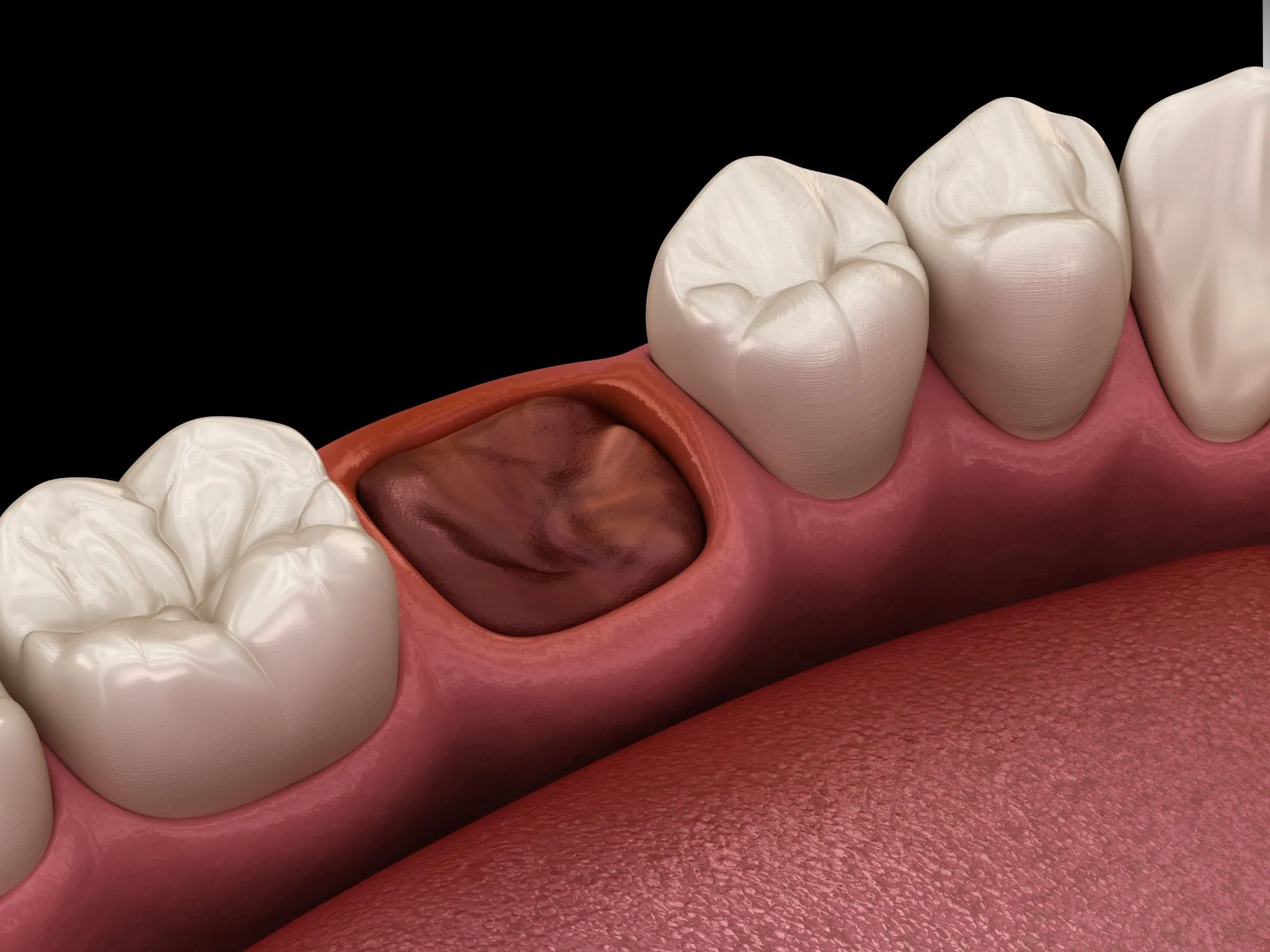

| Visual Appearance | Dark red clot filling the hole. | Empty-looking hole, white/grey bone visible. |

| Smell/Taste | Mild metallic taste initially. | Foul, rotting odor and terrible taste. |

Sensory Indicators Beyond Pain

While pain is the primary driver for seeking help, other sensory inputs provide definitive confirmation of the issue. A prevalent symptom is a persistent, foul taste in the mouth that does not go away with rinsing or brushing. This is often accompanied by significant halitosis (bad breath) that is noticeable to others. This odor arises from the accumulation of food debris and bacteria fermenting in the empty socket, as well as the necrosis of the tiny amount of tissue remaining on the bone walls. It is a distinct "rotting" smell that differs significantly from "morning breath."

Visually, if a patient is brave enough to look into the mirror with a flashlight, the difference is usually stark. In a healthy healing scenario, the socket appears dark due to the presence of the blood clot. In a compromised socket, the hole appears "dry" and empty. One might see a whitish or greyish substance, which is the bare bone, rather than the deep red or purple of a healthy clot. Sometimes, the opening looks like a deep, dark black hole if the bone is shadowed, but it lacks the fullness of a scab. Recognizing these signs early—the radiating pain, the foul taste, and the visual emptiness—allows for quicker intervention, sparing the patient days of unnecessary suffering.

The Path to Relief and Recovery

Professional Intervention and Symptom Control

If the warning signs appear, "waiting it out" is rarely the best strategy. The pain associated with exposed bone is excruciating and can lead to sleep deprivation and dehydration. The most effective route to relief is professional dental intervention. When a patient presents with these symptoms, the dentist will first gently irrigate the socket with a saline solution to flush out any trapped food particles and necrotic debris that are contributing to the pain and infection risk. This cleaning step alone often provides a degree of immediate relief by removing the irritants.

The cornerstone of treatment, however, is the application of a medicated dressing. Dentists will pack the empty socket with a specific paste or gauze strip treated with obtundent medications—often containing eugenol (clove oil), anesthetics, and antimicrobial agents. The relief provided by this dressing is often described as miraculous, turning off the pain signals almost instantly upon contact. This packing acts as an artificial clot, covering the exposed nerve endings and soothing the inflamed bone. Patients usually need to return every 24 to 48 hours to have this dressing changed until the natural healing tissue, known as granulation tissue, begins to cover the bone on its own.

Advancements in Healing Technologies

Looking forward, the approach to managing this condition is shifting from reactive treatment to proactive prevention using advanced biotechnology. Researchers and clinicians are increasingly utilizing Regenerative medicine techniques, such as Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) therapy. In this procedure, a small amount of the patient's own blood is drawn and spun in a centrifuge to concentrate the platelets and growth factors. This golden plasma is then placed into the socket immediately after extraction. It acts as a "super-clot," significantly accelerating tissue regeneration and reducing the likelihood of clot failure.

Furthermore, the development of bioactive materials is changing how sockets are protected. Newer hydrogels and collagen sponges are being designed to not only cover the wound but also to release antibiotics or bone-stimulating proteins in a controlled manner over several days. These materials are biodegradable, meaning they don't need to be removed like traditional gauze. By creating a scaffold that actively fights bacteria and promotes cell migration, modern dentistry is moving closer to making this painful complication a relic of the past. Until then, understanding the risks and seeking timely care remains the best defense.

Q&A

-

What is Post-Extraction Pain and how can it be managed?

Post-extraction pain is discomfort experienced after a tooth extraction. It is usually managed with over-the-counter pain relievers such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen. Applying ice packs to the affected area can also help reduce swelling and pain. For severe pain, a dentist may prescribe stronger medication. -

How does Fibrinolysis affect the healing process after tooth extraction?

Fibrinolysis is the breakdown of fibrin, a protein involved in blood clotting. After a tooth extraction, fibrinolysis can lead to the premature breakdown of the blood clot, which is crucial for healing. This can result in complications such as dry socket, where the bone and nerves are exposed, causing significant pain and delaying the healing process. -

Why is Exposed Bone a concern after dental procedures?

Exposed bone after a dental procedure, such as tooth extraction, is a concern because it can lead to infection and delayed healing. The exposure occurs when the protective blood clot is dislodged or fails to form properly, leaving the bone vulnerable. Treatment may involve medicated dressings to protect the site and promote healing. -

What causes Halitosis following a tooth extraction, and how can it be treated?

Halitosis, or bad breath, after tooth extraction can be caused by food particles trapped in the extraction site or the breakdown of blood clots. Good oral hygiene, including gentle rinsing with salt water and regular brushing (avoiding the extraction area), can help manage this. If bad breath persists, it is advisable to consult a dentist. -

What role do Medicated Dressings play in dental extraction recovery?

Medicated dressings are used to protect the extraction site, promote healing, and alleviate pain. They may contain antiseptics to prevent infection and analgesics to reduce discomfort. These dressings are particularly useful in cases where clot dislodgement or dry socket has occurred, as they help shield the exposed bone and tissues.