Beyond the Smile: Navigating Digital Advances in Orthodontic Aligners

In the realm of orthodontics, a remarkable transformation is underway. Technological advancements are reshaping the approach to improving oral aesthetics and function. As the digital age integrates seamlessly with dental practices, innovative methods offer precise and patient-centric solutions, opening new frontiers in aligning both smiles and modern techniques.

The Digital Revolution in Diagnosis and Planning

The End of Uncomfortable Impressions

For decades, the initial step in any teeth-straightening journey was universally dreaded: the physical impression. Patients would sit in the chair, mouth stretched wide, while a cold, viscous putty filled a metal tray was pressed against their teeth. The sensation of the material expanding toward the throat often triggered a gag reflex, making the minutes spent waiting for it to set feel like an eternity. This analog process was not only uncomfortable but also prone to slight distortions if the patient moved or if air bubbles were trapped in the material.

Fortunately, the integration of optical wand technology has revolutionized this experience. Today, a sleek, pen-sized camera replaces the bulky tray of goo. This device glides comfortably inside the mouth, capturing thousands of images per second to construct a highly accurate topographical map of the teeth and gum lines. The process is entirely non-invasive, breathable, and can be paused at any moment if the patient needs a break. For individuals with sensitive gag reflexes or anxiety about dental procedures, this "touchless" capture method significantly lowers the barrier to entry for treatment. Furthermore, the precision of these digital maps far exceeds what traditional materials could achieve, capturing the nuances of tooth anatomy in high-definition color, which serves as the foundation for a truly customized treatment plan.

Visualizing the Destination Before Departure

Once the intraoral data is captured, it serves a purpose far greater than simple record-keeping. This high-definition 3D model is imported into sophisticated planning software, allowing the orthodontist to choreograph the movement of every single tooth. In the past, patients had to trust the doctor's verbal description of the outcome. Now, they can view a dynamic time-lapse simulation on a screen, watching their current bite morph into the projected final result before a single appliance is manufactured.

This visualization capability is a powerful tool for patient confidence. It transforms abstract clinical goals into a tangible reality. The software calculates the precise force systems required to rotate, intrude, or extrude specific teeth, designing a sequence of transparent trays that are custom-manufactured to execute these movements. This level of backward planning—starting with the ideal finish and working backward to the start—ensures that every fraction of a millimeter of movement is purposeful. It represents a fundamental shift from reactive adjustments to proactive, engineering-based treatment planning, ensuring that the biological limitations and aesthetic goals are perfectly balanced from day one.

Enhancing Workflow Efficiency and Accuracy

The shift from physical plaster models to binary code has drastically improved the speed and reliability of the orthodontic workflow. In traditional methods, physical impressions had to be boxed and shipped to laboratories, often crossing borders. This logistical chain introduced risks: impressions could warp due to temperature changes, plaster models could break, and packages could be lost. Each step added days or weeks to the turnaround time between diagnosis and the start of treatment.

Digital files, conversely, are immune to physical degradation. They do not shrink, expand, or break. A scan taken in a clinic can be instantly uploaded to a lab on the other side of the world, allowing technicians to begin fabrication almost immediately. This efficiency means patients can often begin their transformation weeks sooner than was previously possible. Moreover, if a replacement tray is ever needed due to loss or damage, the original digital file remains on record, allowing for a rapid reprint without the need for a new appointment to take fresh molds. Clinical studies and anecdotal evidence from practices globally suggest that this streamlined digital pipeline reduces chair time, minimizes appointment frequency, and significantly enhances the overall patient experience by removing the friction associated with analog logistics.

The Mechanics Behind the Invisible

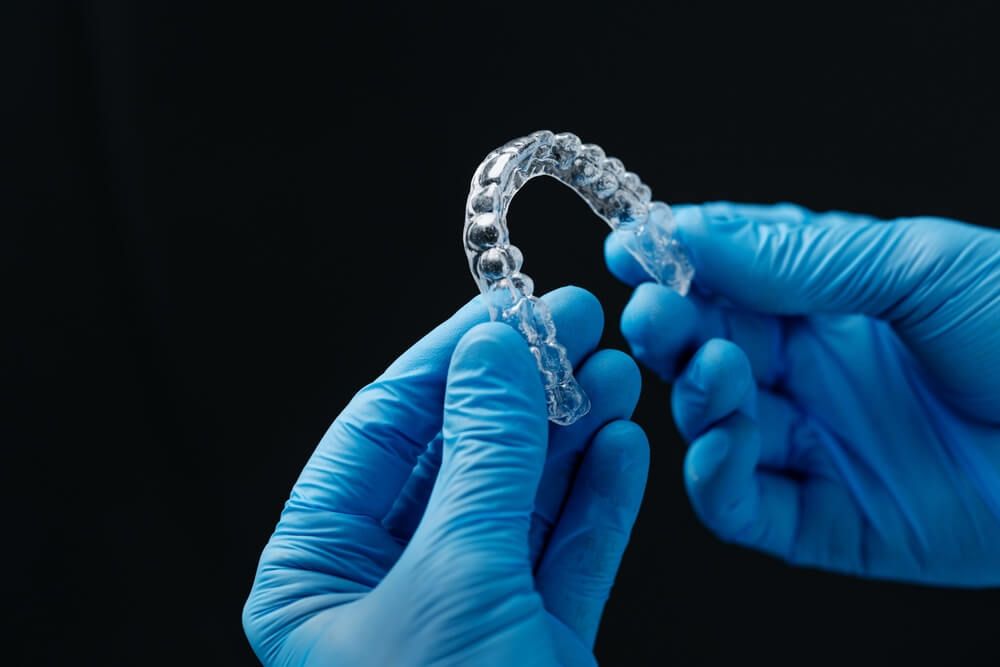

Engineering Grip with Resin Buttons

While clear aligners are often marketed for their invisibility, their effectiveness relies heavily on small, strategic additions known as composite bumps or "buttons." To the casual observer, an aligner appears smooth, but for complex movements, smooth plastic against smooth enamel often results in slippage. To counteract this, doctors bond tiny, tooth-colored resin shapes onto specific teeth. These features act as handles or anchors, giving the plastic tray a surface to grip and push against.

Without these engineered leverage points, certain movements—such as rotating a cylindrical tooth or pulling a tooth down from the gumline—would be mechanically impossible with plastic alone. The shape, size, and orientation of these resin features are calculated by algorithms to deliver the exact vector of force required. For the patient, these bumps might feel slightly distinct when the trays are out, and they create a "snap" feeling when the aligners are seated, confirming that the appliance is actively engaging with the dental anatomy. Although they add a texture to the teeth temporarily, they are the secret workforce that allows removable appliances to rival the effectiveness of traditional fixed brackets, expanding the scope of treatable cases from simple spacing issues to complex bite corrections.

Creating Space Through Gentle Polishing

A common hurdle in aligning smiles is crowding: simply put, there is often too much tooth structure for the size of the jaw arch. Historically, the default solution for significant crowding was the extraction of healthy premolars to create room. While still necessary in severe cases, modern conservative dentistry prioritizes keeping all natural teeth whenever possible. The contemporary alternative is a technique involving the subtle polishing of the enamel surfaces between teeth.

This procedure creates minute amounts of space—often just fractions of a millimeter—between contact points. While the idea of "filing" teeth sounds intimidating, it is performed within the safe outer layer of enamel, far from the sensitive nerve, and typically requires no anesthesia. By reducing the width of several teeth slightly, a practitioner can gain several millimeters of total arch length, allowing crowded teeth to unravel and align without the trauma of extraction.

| Feature | Tooth Extraction Strategy | Enamel Polishing Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Space Created | Large amount (5-7mm per quadrant) | Small to moderate (0.2-0.5mm per contact) |

| Invasiveness | High (surgical removal of healthy teeth) | Low (surface smoothing of outer enamel) |

| Recovery | Requires healing time for gum/bone | Immediate, no downtime |

| Impact on Profile | Can significantly alter facial profile | Maintains existing facial structure |

| Primary Use Case | Severe crowding or protrusion | Mild to moderate crowding or "Black Triangles" |

Additionally, this technique serves an aesthetic purpose beyond space creation. When triangular-shaped teeth are aligned, they often leave small dark gaps near the gumline known as "black triangles." By flattening the contact points slightly, the teeth can sit broader against each other, closing these gaps and creating a more youthful, solid appearance. It is a dual-purpose technique that balances biological conservation with cosmetic refinement.

The Patient’s Role and Long-Term Success

The Critical Role of Discipline

Unlike fixed metal braces which work 24 hours a day regardless of the patient's actions, removable aligners place the responsibility for success squarely in the hands of the wearer. The biology of tooth movement requires constant, low-level pressure to stimulate the cellular activity that remodels bone. Orthodontists generally prescribe a wear time of 20 to 22 hours per day. This is not an arbitrary suggestion; it is a biological requirement.

When the trays are removed for extended periods, the force on the teeth ceases, and the periodontal ligaments act like elastic bands, attempting to pull the teeth back to their original positions. If a patient consistently dips below the recommended threshold, the teeth may not track with the programmed movements of the next tray. This can lead to a situation where the aligners no longer fit, necessitating a mid-course correction or a complete restart of the treatment plan. The "freedom" of removable appliances is a double-edged sword; it offers convenience but demands a high level of self-discipline. Treating the regimen as a non-negotiable part of daily life—similar to wearing contact lenses—is often the defining factor between a perfect finish and a compromised result.

Adapting Lifestyle and Hygiene Habits

Successfully navigating this treatment modality requires integrating the appliance into one's lifestyle, particularly regarding diet and hygiene. Because the trays must be removed for eating and drinking anything other than water, the habit of "grazing" or sipping sugary coffees throughout the day becomes impractical. Patients often find themselves consolidating meals, which can inadvertently lead to better dietary structure and reduced snacking. However, the golden rule remains: clean teeth go into clean trays. Trapping sugar or acid between the plastic and the enamel creates a greenhouse effect for bacteria, rapidly accelerating the risk of cavities and decalcification.

| Scenario | Recommended Action | Risk of Neglect |

|---|---|---|

| Morning Coffee | Remove trays, drink, rinse mouth, re-insert. | Staining of trays; acid trapped against enamel. |

| Restaurant Meal | Place trays in a dedicated case immediately. | Wrapping in napkins often leads to accidental disposal. |

| Snacking | Limit frequency to ensure 22h wear time. | Extending "trays-out" time delays tracking progress. |

| Cleaning | Brush teeth and trays before re-insertion. | Plaque buildup, bad breath, and potential decay. |

Furthermore, the "napkin trap" is a notorious phenomenon where patients wrap their aligners in a tissue during a meal, only for the bundle to be mistaken for trash and thrown away. Developing a reflex to always place the device in its protective case is essential. These small behavioral adjustments—carrying a travel toothbrush, drinking water after coffee, protecting the device—eventually become second nature. While they require effort, they ensure that the path to a new smile is hygienic and free of preventable setbacks.

Securing the Investment with Post-Treatment Care

The moment the final active tray is removed marks the end of the movement phase but the beginning of the most crucial stability phase. The bone and soft tissues surrounding the teeth act like memory foam; they take significant time to solidify around the new tooth positions. Without active retention, the teeth will naturally drift toward their former chaos, a phenomenon known as relapse. This is not a failure of the treatment but a natural physiological tendency.

To combat this, retention protocols are implemented immediately. Options typically include fixed retainers—a thin wire bonded behind the front teeth—or removable nighttime retainers that look similar to the active aligners but are made of more durable material. The fixed option offers a "set it and forget it" solution for the most socially visible teeth, while removable ones cover the entire arch but require the same discipline as the treatment phase, albeit usually only during sleep. Understanding that retention is a lifetime commitment is vital. The biological forces of aging affect every part of the body, including the mouth, so maintaining that perfect alignment requires ongoing, passive maintenance. Viewing the retainer as an anti-aging device for the smile helps shift the perspective from "burden" to "protection."

Q&A

-

What is digital intraoral scanning and how does it benefit malocclusion correction?

Digital intraoral scanning is a technology used to create precise 3D images of a patient's teeth and oral structures. It benefits malocclusion correction by providing accurate measurements that enhance the design and fit of orthodontic appliances, reducing the need for physical impressions and improving patient comfort.

-

How does attachment placement assist in the process of malocclusion correction?

Attachment placement involves attaching small tooth-colored buttons to teeth, which help aligners apply the necessary forces to move teeth efficiently. This technique enhances the effectiveness of clear aligners in correcting complex dental malocclusions by providing additional grip and pressure points.

-

What is Interproximal Reduction (IPR) and when is it used in orthodontic treatment?

Interproximal Reduction (IPR) is a procedure where small amounts of enamel are removed from between the teeth to create space for alignment. It is used in orthodontic treatment to address crowding and improve the fit and movement of teeth, particularly in cases where extractions are not preferred.

-

Why is tray compliance crucial in orthodontic treatments involving clear aligners?

Tray compliance refers to the consistent and proper wearing of clear aligner trays by the patient. It is crucial because the effectiveness of the treatment relies on the trays being worn for the prescribed amount of time each day, ensuring continuous pressure is applied for optimal tooth movement.

-

What role does orthodontic retention play after malocclusion correction?

Orthodontic retention involves the use of retainers post-treatment to maintain the new position of teeth. It is essential because teeth have a tendency to revert to their original positions after treatment, so retainers help stabilize them, ensuring long-term success of the malocclusion correction.