Innovations in Orthodontic Materials: Balancing Compatibility and Durability

In the rapidly advancing field of orthodontics, innovations in material science promise to transform both patient experience and treatment outcomes. Modern approaches emphasize creating components that not only meet structural and functional needs but also ensure a harmonious interaction with biological systems over extended periods.

Redefining the Interaction Between Metal and Biology

The Shift Toward Biological Harmony

For decades, the primary metric for orthodontic materials was mechanical strength. The wires and brackets had to be tough enough to withstand the immense forces required to move teeth through bone. However, the paradigm has shifted significantly. Today, materials scientists are less concerned with brute force and more focused on "biological harmony." The mouth is a highly sensitive ecosystem, and introducing foreign objects like metal appliances requires a delicate balance to prevent adverse reactions. The goal is no longer just to straighten teeth but to do so using materials that the body accepts as a natural part of its environment.

This evolution has led to the development of sophisticated alloys designed to minimize the risk of allergic reactions. Nickel hypersensitivity, for example, has been a longstanding concern with traditional stainless steel. In response, researchers are engineering nickel-free or low-nickel alternatives that maintain the necessary elasticity without triggering immune responses. These modern alloys are often softer and more pliable, capable of delivering a continuous, gentle force that moves teeth efficiently while significantly reducing patient discomfort. This approach treats the orthodontic appliance not merely as a tool, but as a bio-material that must coexist peacefully with soft tissues, minimizing inflammation and promoting overall oral health during the treatment lifecycle.

Engineering for a Hostile Environment

The human mouth is, chemically speaking, a hostile environment for any material. Orthodontic devices are subjected to a constant barrage of challenges: the acidic pH of fruit juices, the alkaline nature of certain vegetables, thermal shocks from hot coffee followed by ice cream, and the mechanical stress of chewing. In such an environment, standard metals can degrade, leading to corrosion. This degradation is not just a structural failure; it can lead to the release of metal ions into the body and a roughening of the material's surface, which impedes the sliding mechanics necessary for tooth movement.

To combat this, advanced testing protocols are used to ensure materials possess exceptional chemical stability. Scientists are analyzing how alloys behave at the crystalline level to enhance their resistance to oxidation and chemical attack. The focus is on creating a hermetic seal at the molecular level that prevents the oral environment from breaking down the material integrity. By ensuring that wires and brackets resist corrosion, orthodontists can guarantee that the force applied to the teeth remains constant and predictable. Furthermore, high chemical resistance prevents the aesthetic degradation of the appliance, ensuring that braces do not look tarnished or worn out halfway through the treatment, which is a major aesthetic concern for adult patients.

| Feature | Traditional Stainless Steel | Modern Beta-Titanium Alloys | Polycrystalline Ceramics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexibility (Modulus) | Low (Very Rigid) | High (Springy & Gentle) | Low (Brittle) |

| Corrosion Resistance | Moderate | Excellent | Superior (Inert) |

| Friction Levels | Low | Moderate to High | High |

| Aesthetic Appeal | Low (Visible Metal) | Low (Visible Metal) | High (Tooth Colored) |

| Comfort Profile | Moderate force delivery | Gentle, continuous force | Bulky but smooth |

The Revolution in Surface Technology

Nano-Level Smoothness and Patient Comfort

One of the most significant friction points—literally and figuratively—in orthodontics is the interaction between the archwire and the bracket slot. When a tooth moves, the bracket must slide along the wire. If the surfaces are rough at a microscopic level, they create resistance, known as binding. This friction requires the orthodontist to apply higher forces to overcome the drag, which often translates to increased soreness and a longer recovery time for the patient after adjustments.

Enter the era of nano-coatings. By utilizing nanotechnology, manufacturers can now apply ultra-thin layers of biocompatible material to wires and brackets, filling in microscopic imperfections on the metal's surface. This process creates a glass-like smoothness that drastically reduces the coefficient of friction. Imagine the difference between dragging a heavy box across gravel versus sliding it across ice; this is the mechanical advantage provided by nano-coatings. For the patient, this technological leap means that teeth can move more freely with lighter forces. The result is a treatment experience that is significantly more comfortable, with reduced pressure on the roots of the teeth and potentially shorter overall treatment times.

The Invisible Shield Against Bacterial Growth

Beyond mechanics, the surface texture of orthodontic materials plays a critical role in hygiene. Braces are notorious food traps, creating nooks and crannies where plaque and bacteria can accumulate. If left unchecked, this biofilm can lead to demineralization—permanent white spots on the teeth—or periodontal inflammation. Traditional raw metal surfaces, while looking smooth to the naked eye, often resemble jagged mountain ranges under a microscope, providing perfect anchor points for bacteria to colonize.

Recent innovations in surface energy modification target this biological challenge. Scientists are developing "hydrophobic" or bacteria-repelling surface treatments. These coatings are designed to lower the surface energy of the material, making it difficult for bacterial adhesion molecules to stick. Some advanced coatings even incorporate bacteriostatic properties that actively inhibit the reproduction of pathogens. By preventing the initial formation of biofilm, these smart surfaces act as a 24/7 passive defense system, working alongside the patient's daily brushing routine. This is particularly vital for younger patients who may struggle with the rigorous hygiene requirements of fixed appliances, helping to ensure that the smile revealed at the end of treatment is not only straight but also free of decay and gum disease.

Beyond Metals: The Era of Composite Resilience

Fatigue Resistance in High-Stress Scenarios

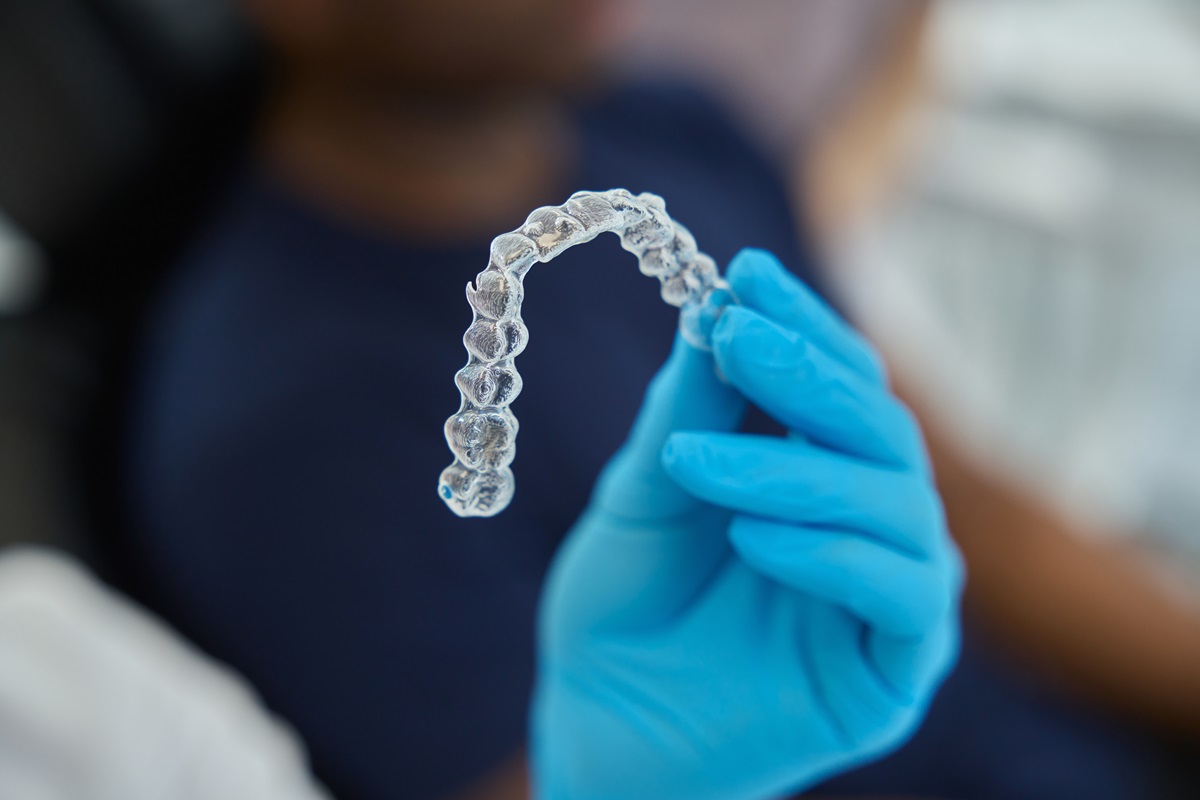

While metals have historically been the kings of durability, they are susceptible to a phenomenon known as work hardening and fatigue failure. Repeated stress cycles—such as the daily act of chewing or the constant removal and insertion of aligners—can cause microscopic cracks to form in metal structures, eventually leading to breakage. As orthodontics moves toward more aesthetic and removable solutions, the industry is turning to advanced composite materials to solve the fatigue puzzle.

These new materials often borrow technology from the aerospace and automotive industries, utilizing fiber-reinforced polymers. For instance, embedding carbon or glass fibers into a resin matrix creates a material that is lightweight yet possesses a tensile strength comparable to steel. Crucially, these composites have superior "fatigue life." They can withstand millions of cycles of flexing and bending without losing their shape or snapping. This is a game-changer for retainers and aligners, which must maintain their precise geometry to keep teeth in position. Unlike metal, which might deform permanently if bent too far, these high-tech composites have an elastic memory that allows them to snap back to their original form, ensuring consistent force application throughout their lifespan.

Customization and Structural Integrity via 3D Printing

The durability of modern materials is further enhanced by how they are manufactured. The rise of 3D printing (additive manufacturing) allows for the creation of orthodontic devices that are chemically identical to their predecessors but structurally superior. In traditional manufacturing, cutting or bending a material can introduce weak points. 3D printing builds the device layer by layer, allowing for the optimization of internal structures.

This means that a retainer or bracket can be made thicker in areas that receive high stress and thinner in areas requiring flexibility, all without creating seams or stress concentrations. This "monoblock" construction significantly reduces the likelihood of mechanical failure. Furthermore, because these materials are often resin-based composites, they offer a warmth and texture that is less abrasive to the tongue and cheeks compared to cold metal. The integration of digital scanning and printing ensures that the material is not just durable in a lab setting, but perfectly adapted to the unique, dynamic environment of the specific patient’s mouth, bridging the gap between mass-produced strength and personalized care.

| Material Type | Best Suited For | Main Advantage | Maintenance Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coated Metal Alloys | Complex bite corrections | Low friction, high speed | High (Must avoid abrasive cleaning) |

| Fiber-Reinforced Composites | Retainers & Aligners | High fatigue resistance (won't snap) | Moderate (Keep away from heat) |

| Polycrystalline Ceramics | Aesthetic-focused patients | Invisibility & stain resistance | High (Brittle, care when eating) |

| Standard Stainless Steel | General, robust treatment | Maximum durability & low cost | Moderate (Standard hygiene) |

Q&A

-

What are biocompatible alloys and why are they important in medical applications?

Biocompatible alloys are metal alloys that are compatible with living tissue and do not cause any adverse reactions when used in medical implants or devices. They are crucial in medical applications because they reduce the risk of rejection and inflammation in the body, ensuring the longevity and functionality of implants such as joint replacements, dental implants, and cardiovascular stents.

-

How does surface energy modification affect the performance of medical implants?

Surface energy modification involves altering the surface properties of materials to improve their interaction with biological tissues. This process can enhance the adhesion, wettability, and bioactivity of medical implants, leading to improved integration with the body and reduced risk of infection or implant failure. It is particularly important in ensuring that implants function effectively and are well-tolerated by the body.

-

What methods are used in corrosion resistance testing of medical devices, and why is it necessary?

Corrosion resistance testing involves exposing medical devices to various environmental conditions to assess their durability and resistance to degradation. Methods include salt spray tests, electrochemical testing, and immersion tests. This testing is necessary to ensure that medical devices maintain their structural integrity and functionality over time, especially in corrosive environments like the human body, which can lead to premature failure if not properly tested.

-

What advantages do nano coated components offer in enhancing the durability of medical devices?

Nano coated components utilize ultra-thin coatings that provide exceptional hardness, wear resistance, and reduced friction. These coatings can significantly enhance the durability of medical devices by protecting against physical wear and chemical degradation. Nano coatings also offer antimicrobial properties, which help in reducing the risk of infection associated with medical implants.

-

Why is material fatigue analysis critical in the development of long-term medical implants?

Material fatigue analysis assesses how materials behave under repeated loading and stress over time. This analysis is critical for long-term medical implants because it predicts the lifespan and failure points of materials used in implants. By understanding material fatigue, manufacturers can design implants that withstand the mechanical stresses of daily use, ensuring patient safety and implant longevity.